[themeone_section type=”boxed” bgcolor=”” txtcolor=”” decotop=”” decobot=””]

INTO THE WILD

INTO THE WILD

It was a few miles from the world’s second northernmost university, near Fairbanks, Alaska, in 1969. It was winter and though it was only mid-afternoon, it was already thirty below and dark enough to see the stars. They were extremely bright, as if closer to the Earth in the vast exposure of the Arctic. All around were white fields of snow, with rows of black spruce pines on rolling hills. On one side of the road a long-haired young man walked alone, his fast-moving silhouette framed by lofty Chena Ridge with its tall stands of white birch. On the other side of the road was the Chena River, frozen solid behind bare willow branches.

The cold didn’t seem to bother him a bit as his long, fast strides ate up the miles. He was headed from the university to his cabin five miles away. Against the searing cold he wore blue jeans, the universal uniform of youth during that time. Their effectiveness was surprisingly enhanced by long underwear, which made an airspace between two layers of cloth. The colorful scarf he wore over his mouth and nose, to keep his lungs from freezing, was from India and he could still smell in it a faint sweet scent of incense.

At that time all over the world young people adopted certain styles and traditions which expressed what they believed in. They liked to wear and do things from different countries and cultures, to show that people were all interconnected. Their wardrobes were wild arrays of different ethnicities and time periods, colorful and exotic and at the same time practical and comfortable. In Alaska their clothes were covered by heavy outer garments, but you could still tell there was SOMETHING DIFFERENT about how they looked. There might be an anti-war button, or a scarf or sash from distant lands, or just the length of hair and the proud way they wore it.

At that time all over the world young people adopted certain styles and traditions which expressed what they believed in. They liked to wear and do things from different countries and cultures, to show that people were all interconnected. Their wardrobes were wild arrays of different ethnicities and time periods, colorful and exotic and at the same time practical and comfortable. In Alaska their clothes were covered by heavy outer garments, but you could still tell there was SOMETHING DIFFERENT about how they looked. There might be an anti-war button, or a scarf or sash from distant lands, or just the length of hair and the proud way they wore it.

He had on the usual army-issue parka which most cabin-dwellers wore, of an olive-green silky material with light reflectors and with a thin band of fur around the hood. These parkas were not as attractive as the down-filled ones from the sporting catalogues, but they were cheap. The white canvas padded boots too, called “Mukluks,” were available for just a few dollars at the army surplus store in town. The fur around the parka’s hood, glittering with frost, made a halo around what showed of his face, just his intense eyes above the scarf and the long uncut strands of hair escaping from it. A peace sign swung from his belt, the world-wide symbol for ending war.

With a kind of reverence they called him “Trashman,” a name he’d gotten for his superior scavenging abilities. He could find anything anyone needed. His special energy helped to hold the community or cabin-dwellers together, and his cabin was its hub. Maybe it was because he looked like Jesus with his long hair that his friends regarded him with awe. But he knew he was no different from the rest. They all looked like that with the long hair that meant non-violence. As far as living in cabins, most people could do what the pioneers had done, but just didn’t realize it.

It was right after Woodstock and everywhere there were young people with long hair and backpacks. Some traveled the world and some dug into the wilderness to find their truth. It was a less cynical age than the one we live in today, less complicated. They said they were looking for themselves, for the meaning of life. Almost all of them believed that if they made the right efforts, or lived in the right way, they could make the world a better place.

That summer a man named Don had bought some property where an old town had stood, including a beautiful little pond, an overflow from the river about a hundred yards away. He’d run into groups of young people from San Francisco, Seattle and Los Angeles, and other places where there were lots of Pacifists, commonly called “Hippies.” They were young and strong but had no money, and very much wanted a wilderness experience. Don had been a city planner in Berkeley, California, one of the biggest hotbeds for Utopian ideals and projects. Maybe he decided to build his own little city out there on Chena Pump Road. He offered the young people a deal that he would provide logs and materials to those who wanted to build cabins, and that they would be allowed to live there rent-free for a year.

Recent high school graduates who’d never built anything in their lives took up the challenge as eager hammers rang in the forest. The structures they put up with inexperienced hands were just as good as those the pioneers had made. What had emerged was a perfect little village of about five oddly-shaped cabins made of nice, new machine-milled logs. Each had a large modern picture window of thermal plate glass, each facing the pond. There was no plumbing or electricity. The place was affectionately known as “the Campground.”

Like many others, Trashman had come to Alaska to find himself, to get away from all things artificial and unreal. Here he’d really been able to spread his wings in a way never imagined before, if only because of the tundra’s wide horizons. There was also the spaciousness of mind of the time he lived in. Here the fever for Pacifism had room to really emerge, even more than he’d seen it before in other places where people wore peace signs and tie-dye. Here there was more time to talk or think about important things, in those tight groups assembled in warm cabins, or on those long walks to town.

About halfway from the university, on the river side of the road, there was a cabin that stood empty. It was open to the elements, with an empty window frame and the door wide open. He knew the reason no-one had moved into it was that it was not insulated, with hollow walls. It would take a lot of work and expensive materials to get this cabin to hold the heat. It was not made of thick logs like the ones at the Campground. It was a thin-walled wood frame building, a shack about eight by twelve feet.

The outside walls were covered with panels pf a black composite material, and the roof was made of bright silver corrugated metal. That’s why they called it the black and silver cabin. He passed it quickly without much interest, having explored it many times before. Again he wondered who could insulate it and move into it. Sometimes the people at the Campground teased a young woman, a pastel coed who lived in a dorm at the university and somehow made it out to the Campground. As a kind of joke they told her she should move into the black and silver cabin and fix it up.

She would come the five miles to the Campground only when she could get a ride. As the cold season intensified she would’ve been prevented from walking that far a distance, because she still wore impractical leather boots that freeze on your feet. In Trashman’s cabin among his friends she would sit quietly in a corner, taking in everything she saw and heard with complete fascination. Her glaring pink ski jacket with dark fake fur trim contrasted sharply with the subdued, smoky colors worn by those who lived in the woods.

Her name was “Sky,” a name she’d given herself. She had very long chestnut-colored hair which she wore in thick braids around her head. Even with the braids she weighed barely over a hundred pounds. They thought she was quite pretty but sort of odd, keeping to herself as she spent much of her time thinking and writing in French. She had a French boyfriend in France and wrote to him almost daily in that foreign language. Trashman doubted that she’d make it out to the Campground again until spring.

He hurried around the last bend as temperatures dropped so quickly that he was unconsciously careful not to take a deep breath. The scarf covering half his face was frozen stiff with frost from his breath, as were his eyelashes and eyebrows and strands of his long hair. The areas around his cheekbones and the fronts of his upper legs were numb, but he knew he was fine. He was now less than a mile from the Campground.

Chena Pump Road, with its new black asphalt and bright, newly-painted lines, seemed incongruous with the raw wilderness on either side. The landscape was incredibly silent and still, since there was no wind to stir the dark spruce branches and shake loose their mounds of billowing snow. Everything was muffled and very peaceful. The loudest sound was of his canvas footsteps squeaking on a thin layer of snow on the side of the road, where he preferred to walk rather than on the asphalt. The only other sound was of his careful breathing through the frozen scarf.

Now the Northern Lights, those marvelous ribbons of light, whipped across the sky in giant arcs. They were so beautiful, in some places pink or light green. They moved so fast yet made no sound, except for a slight vibration which he wasn’t sure if he heard or felt. Catching his breath he stopped for a minute to take it in. It was wonderful to feel the liberty and luxury of so much empty space. Turning around slowly he reveled in the night sky with its millions of piercing stars that seemed so close. Most of the people who lived at the Campground had grown up in cramped apartments; this was like Heaven to them.

He carefully took a deep breath of the extremely cold air, enjoying a sort of fragrance that it had and the way it seemed to cleanse the inside of you. The last few month since his arrival here in the spring had been the happiest of his life. He seemed so accustomed to all this, as if he’d always lived in the North. Yet this was going to be his very first winter, as it was for almost all the people at the Campground.

There was no cloud cover, which made the Earth lose heat fast. During the brief time it had taken him to walk the last mile, temperatures had dropped ten degrees. There was real danger out here, real adventure. People had died under these conditions, probably some of them not far from here. But he and his friends bore the cold very lightly, as if surviving it were some sort of game. They took great pride in how fast they could learn to build a fire or to live in a cabin. It was an art form for them, a spiritual quest, to live happily without plumbing, electricity, or cars. Some viewed themselves as refugees from the modern world, looking for something deeper and more meaningful than what machines could make.

Mighty ideas were pushing into people’s thoughts the way aggressive sperm enter an egg to make life. Visions of a just world were ignited, where war, hunger and poverty were barbaric remnants of a brutal past. The concept of universal brotherly love was not always enunciated, but it was deeply felt. Peace drums were heard inside the cabins, inside the rock songs on cassettes that were played until they were in shreds.

A burgeoning Peace Culture exploded on the world. People who’d never met grasped a hopeful vision with one heart. The drums of all the nations was their heartbeat, Peace Drums signaling an end to war. It was a form of music anyone could learn and could afford. Spontaneous “drum circles” of random strangers performed where people gathered. The drummers came from every class. Some had brightly- decorated drums from exotic places. Others had drums of clay or wood they’d made themselves, or even played white plastic buckets.

Young men and women chose to look past the atrocities of history and believe that mankind was good and worth saving. In wearing bright colors, or in traveling or studying in search of solutions, they chose to believe that even such a terrible mess as this world could be repaired. What they felt inside seemed to them to be strong enough to conquer injustice, heal devastation.

You could see where rabbits had eaten the bark of the willows and other plants right above the snow line. Each year when the snow melted, that’s how you could tell how high it had been. It didn’t snow that much in the interior of Alaska, which was a relatively dry area. The infrequent snow left about two or three feet on the ground for about seven months of the year. There was also very little wind. Both weather conditions made it much easier to keep warm than if there had been dampness or a wind chill factor. In most cases, the right layers of clothing were all you needed to assure relative comfort.

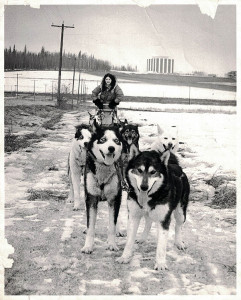

There were moose in the wooded areas and even bears and wolverines, or possibly wolves for all he knew. He’d never seen a wolf out here but those Malemute sled dogs sure sounded like them, and most of them were in fact part wolf. He’d seen a few black bears, and gigantic moose were frequent visitors at the pond where he lived. The much smaller wolverines were more reclusive, but were reported to be the most vicious and aggressive if confronted. He’d never seen one, and didn’t know anyone who’d ever seen one, but he’d been warned to stay clear of wolverines.

There hadn’t been any grizzly bear sightings in the area for maybe decades, but you never know… It wasn’t out of the realm of possibility that you might encounter something wild that was hazardous. But he didn’t fear wild animals, only the civilized ones. They were the ones that devastated the Earth with machines, money and war. They were the ones who needed to find better ways to adapt, in order to survive their own violence. In Nature things were much more simple; what you saw was what you got.

He walked into what would’ve been darkness but for the brightness of the snow. There were no street lights or house lights in the distance toward the Campground, no traffic lights. No electric wires or metal pipes reached the rustic cabins there, as far as anyone knew. Outhouses were used and kerosene lamps, just as had been done on that same spot almost a century before.

The place where the Campground cabins had been built had been the site of a tiny goldrush town called Chena, which, in the 1912 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, was more prominently-marked than the modern-day town of Fairbanks a few miles away. As Fairbanks became the main center and Chena was on the wrong side of the river, accessible only by boat or in winter over an ice bridge, the town had slowly become abandoned and the cabins had fallen into ruins. The cabins had been taken apart for firewood until only a few foundation logs remained.

As he approached further down Chena Pump Road, he began to see a very dim light through some trees. It was not the glare of an electric light but a barely-visible flicker, really just a glow, contrasting slightly with the frozen wilderness around it and the black shapes of trees. It was a kerosene lantern or a candle set in one of the picture windows.

He could not see the cabins yet but he could see and smell the smoke from their chimneys. To the left of the road he could now see the wide Nenana River, where it was joined by the Chena River. Its frozen expanse stretched pristine and white toward the south and west, to a horizon headed in the direction of Mt. McKinley, the tallest mountain in North America. The Campground was where Chena Pump Road turned uphill to the right, and went back toward the university along the edge of Chena Ridge.

In a way being on the end of that loop of road, which curved around at the Campground, was like being on the edge of what was called civilization. Here the machines ended, the wires and pipes, the blare of TV. Looking down the frozen river you could actually imagine that for five hundred miles in several directions there might be no human habitation except for a few seasonal native fishing villages. The river, trees, meadows and rolling hills looked just as they had for thousands of years. It was a good feeling to know that everywhere nearby there were patches of untouched ground.

Coming Next: TRASHMAN’S CABIN

[/themeone_section]